The first in a continuing series (Click the ‘Tales From Topside’ category heading above to see the rest). Doug Podgorny was area manager ovens up until the very end. With 25 years between the coke plant and mill, he watched things start to unravel but had to stick around to see it through. Never before has this story been told, first hand. Stick around for more.

First, a little history…

In 1945 the United States produced 72% of the worlds steel. America’s mighty war machine, the building of the nation’s infrastructure, expanding out great cities and at least one car in every garage required massive amounts of steel. One could argue that in this time period America’s ability to produce these massive quantities of steel provided one cornerstone of what made America great.

However, as other countries continued to expand their industrialization world wide, steel production grew. Peak US steel production appears to have been recorded in 1973 which then contributed to approximately 20% of the world totals. Recessions in the late 70s/early 80s saw US steel production cut to half of the recorded peak in 1973 by 1982.

Simply put, the American steel industry as it existed was in its dying throes by the mid 80’s. Wisconsin Steel, across Torrence Ave, was one of the first to go belly up in 1980. We at Acme took the demise of our neighbor in stride as the word was Wisconsin was a terribly managed operation. We all felt confident that Acme had some pretty smart dudes running the company.

Acme had become the conglomeration of a coke plant on Torrence, a blast furnace on Burley and a BOF to produce steel on Perry Ave, in Riverdale. It had several distinctions when compared with the giants like US Steel, Inland and Bethlehem Steel. Acme was the smallest integrated steel mill in the United States. ‘Integrated’ meaning that the processing plants for all the raw materials necessary to make steel were owned by the company. The norm is that all these processes reside on the same property – Acme’s was spread across three different locations!

The big players focused on what I call “vanilla steel” – the basic steel made for skyscrapers, bridges, rails, etc. They were able to produce millions of tons of this low margin but high volume steels. Acme’s focus was on mid and high grade carbon steels (over 400 different types) that the big guys didn’t want to bother with.

Acme’s old guard executives also had implemented a downstream corporate integration by acquiring Universal Tool and Stamping (largest auto jack producer), Alpha Tube and several packaging companies (steel straps and tools for binding whatever you wanted to) which became Acme Strapping. These companies consumed 40% of our steel production.

Still, Acme struggled with the rest of the industry thru the 80s and 90s. We had a brush with bankruptcy in the mid 80’s. It was averted when the union agreed to concessions and we plugged along with very small profit margins. By far, the bulk of capitalization projects were directed towards the technology to improve environmental protections. Don’t get me wrong, those emission controls were extremely important! The industry had operated with impunity polluting the air and water long after they knew the inherent dangers. At least for Acme, production upgrades and wholesale technological improvements toward production would have to wait.

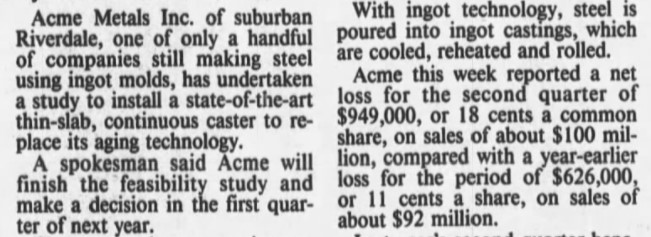

By 1994 the “OG” had been either retired or moved to the board of directors and a West Point grad was hired as the CEO. He was big on modernization and with more union concessions convinced the board to build the most powerful modern continuous caster in the world (until Germany built one bigger the next year). Acme borrowed over $400 million for the undertaking. This was my first “oh shit” moment.

During my stint as Pickling Area manager I was appointed to a team to answer customer complaints. During visits to customer sites, they would always be sure that we could espy coils of steel (mainly from foreign producers) as we passed. Most of these complaints could have been addressed by updating the equipment we had. My opinion was if you were going to borrow that much money, we should be solidifying what we had rather than chase other markets. This new caster would put Acme in the class of the biggies as far continuous caster tech went but I thought it would do very little for our niche markets. But away we went.

The new caster was plagued with construction delays. Training a workforce, implementing a team concept (where the team essentially replaced the old management directed supervision) and the startup woes that would be expected in a project of this magnitude held the project up for months. Unfortunately, the West Point dude had totally missed the impact that cheap imports would have as the domestic demand for American steel was shrinking. Cheap steel was being dumped in massive tonnages from the defunct Soviet bloc, China, Japan and even Brazil! An industry coalition went to Washington to petition for tariffs based on foreign dumping. I was told by a gentleman on that team that Washington’s official response was “the strong will survive” and essentially turned their backs on the primary American Steel industry. Mini -mills and electric arc furnaces would be the future.

In 1997, as Acme was hit by seven consecutive quarters of losses and stock falling from $17 per to $2 we began to hack the workforce. Cutting 20% happened and we began to train Riverdale employees at the coke plant. We were pretty confident at the coke plant and I mistook the transferring of people as an unofficial sign that no matter what happened to the rest of Acme, the coke plant would go on. We did run an extremely tight operation. I felt we had some of the best talent in the coke business from top notch performers in instrumentation, maintenance, management, and operational groups with over 90% of the hourly workforce engaged and conscientious. The batteries had been rebuilt and were being operated properly. We produced a world class product and could have sold coke anywhere if we no longer had to feed our blast furnace. Our management team met regularly and all felt the coke plant would survive. Except….if nobody’s making steel, you don’t need coke!

Steel demand was not rebounding and losses mounted. Being saddled with the repayment of the $400 million exacerbated the losses and continued to bleed any profit we could have realized. In 1998 Acme formally filled Chapter 11 with another $100 million borrowed from Bank of America to fuel the reorganization. This was my second “oh shit” moment.

The coke plant didn’t sit still though! Guided by our well connected division manager we began to convert half our capacity to making foundry coke. This was a whole different animal – different coal blends, different heating cycles. Foundry coke is also much harder and much larger than furnace coke so even the handling was different. But we didn’t have enough time to refine our product and were able to sell very little! Most foundries were happy with their current suppliers. It was a very tough market.

Even through all that we all still thought we had a fighting chance. Morale wasn’t exactly high and the unofficial conversations revolving around impending doom got more frequent. However, most were able to maintain a degree of professionalism. We brought out purge plans around August 2001. Basically, being able to safely evacuate any coke oven gas from the entire process and plant. We had purged parts of the system to facilitate maintenance, vessel or piping replacements but NEVER the entire plant! That’s a double “oh shit” – this could be it!