The following article is taken from the Feburary 1965 edition of the Interlake Steel Corporation Reporter. This was volume 2, number 2 for this intracompany newsletter. The article is uncredited; the only by-line is on the last page of the newsletter, stating only “Published monthly by the Public Relations Department, Interlake Steel Corporation”. Director: H. Harry Henderson. Editor: Art Grimm. Assistant: Eleanor Zine. Photographers: W. A. Birkle, Ken Goetz, Dave Schultz.

The original article continued on, going into detail about a visit to the furnace plant. This is a truncated version, focusing on the coke plant.

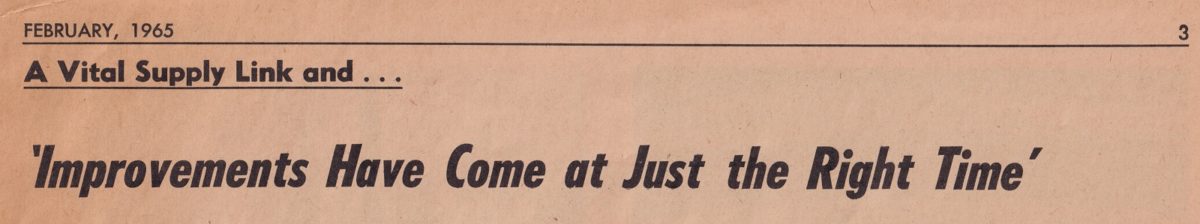

The largest of Interlake’s three blast furnace plants, the South Chicago operation spans over a 376-acre site 15 rail miles and 8 highway miles from the Riverdale plant. It straddles the Calumet River, with the coke oven plant about a half-mile from the river to the West, and the blast furnace plant directly on the East bank.

Linking the operations is a giant suspension bridge spanning the Calumet river.

The bridge system begins underground at the coke oven wharf, rises far about Torrence Avenue, crosses a field then makes an abrupt climb to the minimum of 126 feet above the water level. This gives ample clearance for boats plying the inland waterway. Towers above the structure range near the 200 foot level.

Once over the river the bridge dips sharply to a coke screening plant which services the blast furnace operation.

Coke Conveyor Inside

Inside the 3800 foot long bridge, built in 1957 to speed flow of materials between the operations, is a belt conveyor carrying a stream of coke to fuel the blast furnaces. The bridge also carries an 84-inch pipeline for transfer of blast furnace gas; a 36-inch pipeline for transfer of coke oven gas; a 16-inch pipeline for natural gas; and a pneumatic tube for speedy delivery of iron samples to laboratories on the coke oven side.

And, if you feel like a good 20 minutes hike, a walk extends the full distance inside the bridge.

The plants at either end of this vital supply are pioneers of their type. The coke oven operation dates to 1905 , when it became the first property of By-Products Coke Corporation, later to become Interlake Iron Corporation. The blast furnace was acquired by Federal Furnace Company in 1915.

Steady Growth Since

Since that time the two operations have grown as one, the coke oven plant as a supplier of fuel for the blast furnaces, the blast furnaces as a growing supplier of merchant iron to the steel industry, foundries and others.

Modernization and renovation have been going on constantly, with the peak period occurring in the 1957-60 period when the suspension bridge, coke screening plant, an ore bridge, a storage bridge, the new coke ovens, a new sinter plant, a new boiler house, modern materials handling equipment, and other improvements were made at the cost of more than $30 million. More recently, a new pig iron casting system and a new scrap processing facility were installed; one of the blast furnaces was relined and the other enlarged and relined. A new plant office building is now being constructed at the blast furnace operation to replace an older building at the coke plant site.

“Though these improvements were undertaken to improve Interlake Iron’s ability to serve it’s customers, they’ve come at just the right time for the merged corporation,” said Mr. Lowe [Earl F. Lowe, superintendent, furnace plant]. “With them, we’ll be in a much better position from the outset to meet our increased iron production needs,” he added.

The coke oven and blast furnace operation centers on two batteries of 50 coke ovens, each capable of supplying more than 600,000 tons of coke yearly; the two blast furnaces, a sinter plant capable of keeping the blast furnaces fully supplied, if need be; a new scrap processing facility; a pig casting plant; extensive dock space for receiving iron ore, and the materials handling equipment necessary for fast and efficient movement of raw materials and finished products.

Two get a closer look at the South Chicago operation, the Reporter visited the two plants recently, beginning with the coke plant.

Coking a complex operation

Seeing a coke plant for the first time, the visitor is likely to be highly impressed with the size and complexity of the operations required to perform what at first appears to be a simple task – the conversion of coal into coke to make fuel for blast furnaces, and the production of coal chemicals from the coke oven gas.

The first coke plant requirement is a vast amount of coal to feed the coking ovens, each of which takes a 17 1/2 ton charge. In all, the 100 ovens will hold 1,750 tons.

The coal arrives in rail cars holding from 75 to 95 tons each from the Olga Coal Company, a West Virginia mine owned 37% by Interlake, and from other sources.

Use three types of coal

“We use three types of coal,” reports Roger Nagan, coke plant superintendent. “These must be stockpiled separately then blended to provide the specific types of coke needed at the blast furnaces.”

The coal cars are emptied into a huge rotary dumper which tips the entire car. It is then delivered by conveyor to an overhead hopper to await stockpiling.

It is here that the first of several spectacular operations – to the visitor, at least – occurs.

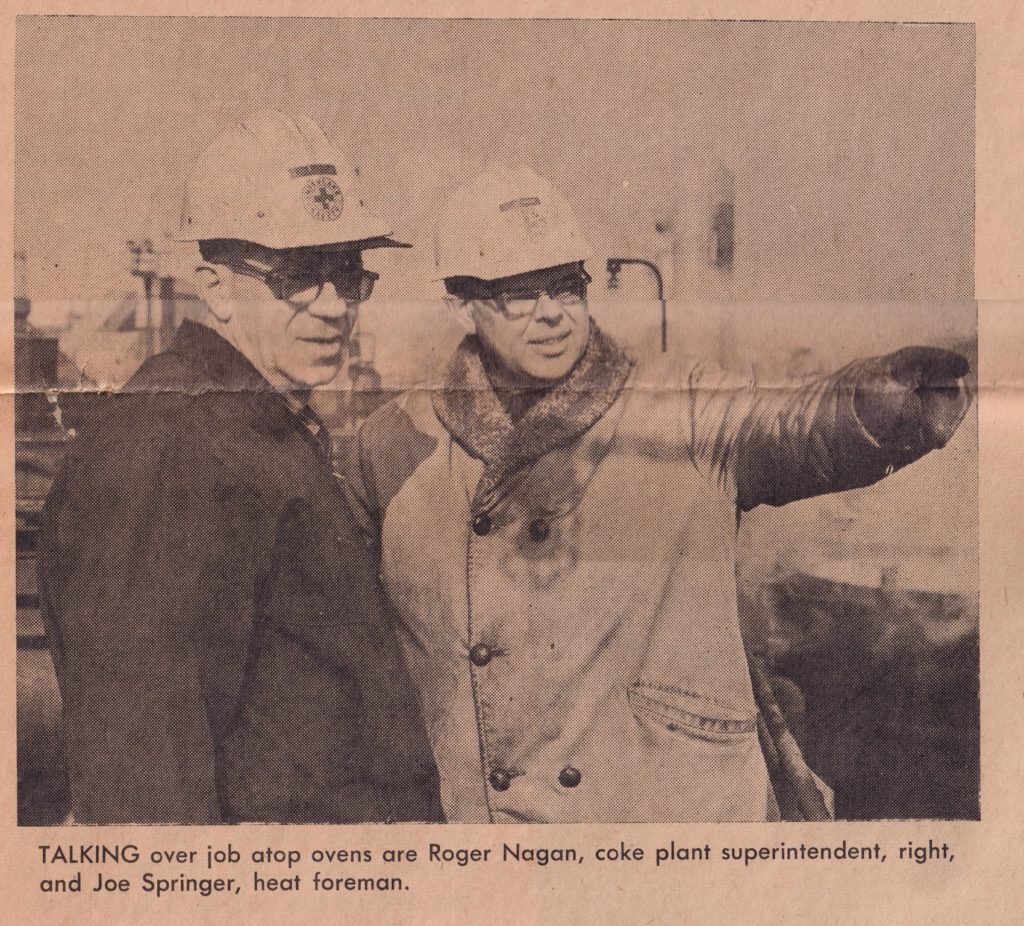

This takes place as two huge big earth moving machines, each weighing 38 tons and carrying 20 tons of coal, alternate in taking the coal to one of three stockpiles in the plan’t coal piles.

After the big twin-motor, twin-drive earth movers are filled with the coal, they roar out over the coal piles to deliver their load. Racing faster than you’d think such giants could move, they dump their 20-ton load and are back for a refill in four minutes flat.

At these speeds, the machines can stockpile between 300 and 350 tons of coal per hour.

Furthermore, the hug tires spreading under the 55 ton burden, compact the coal piles, helping to prevent circulation of air and possible waste due to oxidation.

“The earth movers are also charged with supplying our ovens with coal from the piles,” reports Mr. Nagan.

Coal to be coked is brought to ground level hoppers by the machines, where it is fed into the plant’s crushing and mixing facilities. It is first pulverized by huge hammers, then mixed in a second facility, to proper blends for the upcoming coking operation.

It then travels by conveyor to a huge hopper rising about 200 feet above the coke ovens.

It is now ready for coking. And the ovens in which this is done are the second of the spectacular sights at the plant.

A coke oven, if you haven’t seen one, is rectangular, and lined with silica brick. It averages about 18 inches wide, but is 12 feet high and 40 feet long. Self-sealing doors weighing 4 tons are at the end of the oven, and vertical heating flues extend up the sides. One hundred of these, lined up like books on a shelf, are in the South Chicago complex. Beneath the ovens are huge heat exchangers for heating of the air and gas used as fuel for coking, and above the ovens are huge mains which carry off the coal chemicals resulting from the coking process.

The entire complex is operated by a crew of 12 men and its “nerve center” is a control panel deep in the oven structure.

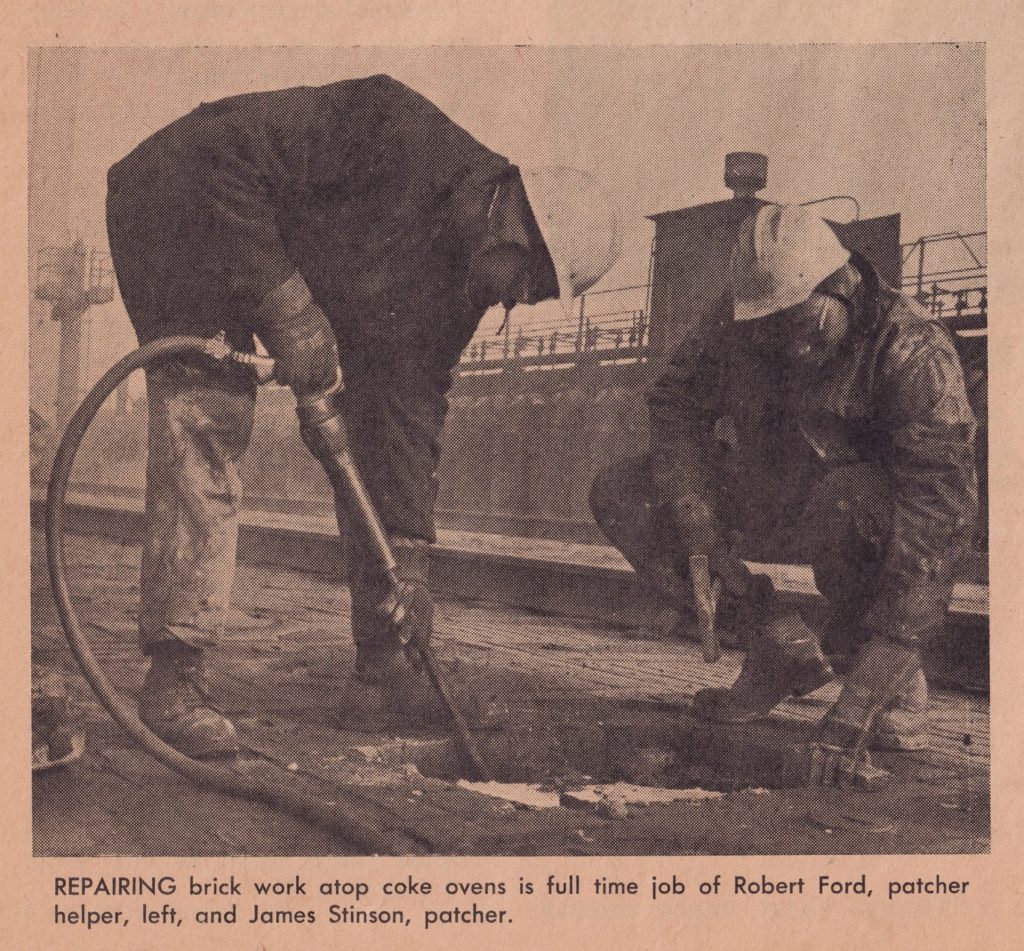

Atop the ovens are two “larry” cars on rails, which keep the ovens charged with coal.

‘Pushing’ – ‘Quenching’

To one side of the ovens near ground level is a large “pusher car,” also on rails. It is equipped with a huge steel ram which pushes the coke out of the ovens. A “quenching car” on the other side receives the coke and delivers it to a quenching station. Here, some 8,000 gallons of water is showered down onto the coke, cooling it from 1,800 degrees to about 150.

It is then dumped onto the coke wharf for delivery to the blast furnace plant screening stations, where it is screened before going to furnace bins.

Blast furnace gas is fuel

“Fuel for the coking operation,” said Joe Springer, heater foreman and 40-year Interlake veteran, “is blast furnace gas generated by our furnaces across the river. Though it has a low BTU (about 90-100 per cubic foot), as compared with coke oven gas (550 or more), it is easier to handle, safer and considerably less expensive.

“And expense counts,” he added, “because we use more than 60 million cubic feet of blast furnace gas a day now, and this will likely go higher as we increase our ‘pushes’ per day to supply the added coke needs of our furnaces. This will mean hiking our present day production from about 1,700 tons a day to around 1,900.”

The 17 1/2 tons of coal fed each oven at a time yields about 12 1/2 tons of coke and takes from 16 to 18 hours for proper coking. Oven temperatures are about 2,400 degrees.

The rest of the coke oven yield is gas, from which tars, ammonia, and light oils are obtained by fractionation in the operation’s by-products plant.

The tars and light oils are sold as is, and the ammonia is converted to ammonium sulfate by passing it through a weak spray of sulfuric acid. It makes an excellent fertilizer compound.

Coke Oven Gas Sold

Most valuable of the coke by-products, however, is the refined coke oven gas from which these coal chemicals have been removed. Produced in vast quantities, up to 190,000 cubic feet from each “push” of coke, it is sold to a steel plant across the Calumet near the Interlake blast furnace plant.